Learn why we don't want these changes past.

Summary on Venezuela

Caracas, 20 November 2007

By Enrique ter Horst

The National Assembly submitted on 2 November to the National Electoral Council (CNE) the text containing changes to 69 articles of the Constitution, with the request to organize a referendum to approve or reject the proposed “reform” of the Constitution championed by President Chávez. The CNE has been organizing the referendum for 2 December, but published the full text of the changes on 12 November, allowing voters only 18 days to study the changes and make up their minds on how to vote.

Separate votes are to take place on two blocks of articles;

the first, called A, includes the changes originally proposed by the President, which were analyzed in the last summary, plus 13 new ones proposed by the Advisory Commission created by Chávez, and which include:

- lowering the voting age to 16;

- weakening the protection of intellectual property;

- adopting a foreign policy geared to “establishing a pluripolar world, free of the hegemony of any imperialist power center..”

- promoting integration and confederation (with Cuba?) and categorizing the foreign service as a “strategic activity of the state”;

- defining the socio-economic regime of Venezuela as based on “socialist, anti imperialist and humanist principles” and dropping the present principles of “social justice;

- democracy and free competition”;

- making future constitutional amendments and reforms more difficult by increasing the number of voters able to initiate them from 15% to 20% (amendments) to 25% (reform) and to 30% for the convening of a Constituent Assembly, as well as increasing in all cases the minimum number of participating voters, but allowing the CNE to shorten the holding of a referendum from “in” 30 days to “within” 30 days.

The 23 articles of block B, described as the contribution of the Assembly but in fact also reflecting the views of the President, and produced only at the end of the third parliamentary discussion, include: the suppression of the words “of all persons” after the words “rights and freedoms” to be guaranteed by the state in compliance with the principle of non discrimination.

significant increases in the percentages of voters required to request the organization of consultative (from 10% to 20%) and recall (from 20% to 30%) referenda, the annulment of laws (from 10% to 30%), as well as the annulment of laws promulgated by the President under enabling laws (from 5% to 30%);

the participation of administrative staff in elections to choose University authorities;

the transfer to the central government of the income of states derived from non-metallic minerals, salt flats, and roads and highways

the functional subordination of state comptroller offices to the central National Comptrollers’ office;

the substitution of civil society and of the law faculties as members of the postulation committees to select Supreme Court and National Electoral Council magistrates by spokesmen of the Poder Popular;

the exclusive authority of the President of the Republic and of his Council of Ministers to declare all states of exception (emergency) suspending constitutional rights, without any time limitation, eliminating the present requirement of securing approval of the decree declaring the state of exception by parliament within 8 days of having been dictated, as well as its submission to the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Tribunal of Justice for its opinion on its constitutionality, canceling the guarantee of maintaining in such states the rights to due process, information and the protection of the remaining intangible human rights, and of ensuring their conformity with the International Pact of Civil and Political Rights and the American Convention of Human Rights, entrusting solely the President and his ministers with the decision of when the circumstances that gave rise to the imposition of such states of exception have ended.

The text of the proposal ends with 15 transitory provisions of which the most important ones are the first, listing fifteen laws constituting the backbone of the new revolutionary legal framework, and the ninth, authorizing the President to regulate by decree “the transition towards the socialist economy model” even before the principles included in article 112 of the new Constitution are developed.

Many expect the nationalization of all private banks, the cement producers and of the POLAR beverage and food conglomerate in early 2008, should the “reform” be approved.

The laws listed in the first transitory provision are the laws of the Poder Popular, of the Promotion of the Socialist Economy, of the Political and Territorial Organization of the Republic, of the Central Bank, of the National Fund of the Poder Popular, of the Municipal Branch, of the Foreign Service, of Hydrocarbons, of Gas, of the punishment of the crime of torture, of Labor, of the System of Justice, of the Social Security System, of the establishment of the Fund for Social Stability for self-employed workers, and of Education.

Chávez has announced that more than a hundred laws will be promulgated soon after the “reform” has been approved. It will be recalled that the Enabling Law authorizing the President to legislate by decree only lapses in mid 2008.Chávez’ radical proposal has forced Venezuelans to define themselves as either democrats opposing him and what he stands for, or old fashioned communists, fascists and/or opportunists supporting him.

This sounds caricaturesque, but is exactly what is happening.

Polarization of the electorate suits him well, as his popularity is more and more concentrated on the remaining affection of the poor in light of his dismal performance as a ruler. His campaign is designed to deepen polarization along support or rejection of his person (“SI, con Chávez”, “SIgue con Chávez”), threatening in his first campaign speech the “oligarchs of the east of Caracas” with a million people who would not leave stone on stone if they attempted another coup against his government.

Not surprisingly the government has shown little interest in allowing for an open discussion of his “reform” proposal, and the televised debates that had been foreseen for the second half of November have been cancelled.Chávez’ old magic is not working as well as it used to.

After almost nine years in power he has not addressed the worsening security situation in the poor barrios, the main concern of over 60% of the population, and the scarcity of basic food items like milk, meat, sugar and cooking oil is becoming more acute by the week. Although large shipments are supposed to arrive from Brazil before the referendum (a ship carrying Brazilian cattle sank a few miles outside of Puerto Cabello last week, and the dead animals have been washing ashore since), rice and pasta are expected to be the next to disappear from the shelves.

The MERCAL food distribution network is close to collapsing, most of its subsidized products finding their way to the black market, and two out of three of its outlets are simply not functioning, says Jesus Torrealba, the host of the popular Radar de los Barrios radio and TV program.

Many of the Cuban doctors of the Barrio Adentro program only survive because the people provide them with food and money, also according to Torrealba.

The country had been stunned into paralysis by the “reform” proposal, but since the first week of November Venezuelans appear not to be dealing with anything else. Every day student marches take place in the main cities, in particular in Caracas, Merida, San Cristobal, Maracaibo, Valencia, Barquisimeto and even Barcelona-Puerto La Cruz, a Chávez stronghold. As of tomorrow these marches are expected to grow larger as people from all walks of life start joining them.A new leadership is fast emerging from the student movement. Intelligent, committed, courageous, highly articulate and from all social classes.

They represent a new, broader-based opposition movement that includes mainly the lower middle class and the poor who had not been politically active, many formerly part of Chávez’ political base. The government had not used violence in order to disperse the marching students but has now started to repress them with its gangs of hoodlums on motorcycles, as shown on a particularly damning video of the 7 November armed persecution of protesting students on the campus of the UCV (Universidad Central de Venezuela), and which ended with three students wounded by bullets.

The movement has only continued to grow and gain speed. It is against this background that General Raul Baduel (no longer active, but until July Minister of Defense and a Chávez loyalist and close friend) shook the country by stating that the “reform” proposal constituted a coup d’ etat and that the Executive and the Legislative had kidnapped the constituent powers belonging to the people.

He also called on his former comrades in arms to carefully read the “reform” proposal and reflect on its contents, and on all Venezuelans to vote NO on 2 December, as it is the last opportunity, he said, to secure democracy peacefully. General Baduel, has changed the internal dynamics of the chavista movement by separating allegiance to the Comandante- Presidente from the substance of the “reform” proposal.

General Baduel, who is close to the PODEMOS party (particularly to Didalco Bolivar, the governor of Aragua) has been speaking to groups in the interior of Venezuela and has used a second press conference to call on Chávez to withdraw the “reform” proposal, and on the Supreme Tribunal of Justice to decide in favor of one of the many requests it has received to cancel the referendum.

Baduel is one of the original members of the “Saman de Guere” oath administered by Chávez to overturn the previous political order. He is highly respected in the Armed Forces for his principled leadership and professionalism, and he has a significant following of officers after a successful 30 year career in the army.

In addition, his youngest daughter is Chávez godchild. His statements have opened the floodgates to many Venezuelans who now feel free to openly denounce Chávez and his policies, and for a large number of Chavistas to follow the path of “Chávez si, reforma no”, as chavista leader Gina Gonzalez of the Telares de Palo Grande barrio proposes.

Baduel is bound to play an increasingly important role in the future.The long interview given last week by former First Lady Marisabel Rodriguez on Globovision also calling for a NO vote, and the famous “Porqué no te callas?” (“Why don’t you shut up?”) hurled at Chávez by King Juan Carlos at the Iberoamerican summit in Santiago de Chile, also appear to have had an effect in strengthening a perceptible growth in the numbers of those rejecting the “reform” of the Constitution.

Many things are forgiven in Latin America, but not being the object of ridicule. Hinterlaces’ latest poll finalized in the first week of November puts the YES at 45% and the NO at 43%, with an abstention of 39%. The study also shows that if the percentage of those abstaining came down to 25% the NO would win with a difference of 14 points.

DATOS, also a very respected polling company, puts the NO at 41% and the YES at 33%. Several polls show that a majority believes that the reform proposal benefits the President more than the country. One opinion poll outfit close to the government puts the YES ahead by 66%.The intention to abstain is still running high, however, and only a few of the opposition spokesmen have called on voters to go out and vote NO.

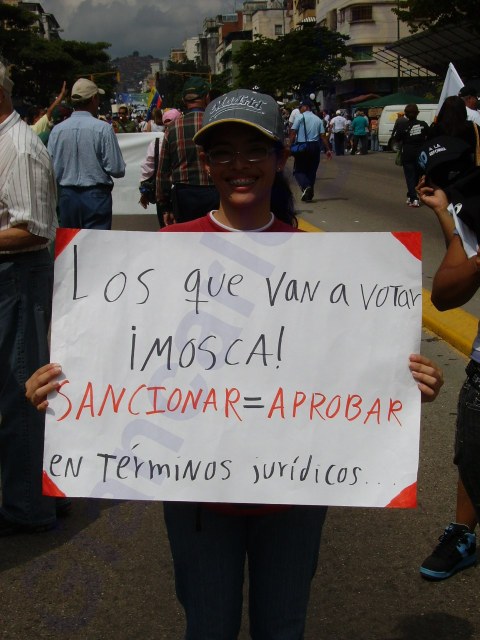

Distrust of the CNE continues to be strong, and the “reform” route is recognized by most as illegitimate, but the encouraging trend favoring the NO could change that soon. In addition to Petkoff, Baduel and Ismael Garcia of PODEMOS, Manuel Rosales has now also called on voters to do so, and the students will take the same position on the occasion of their march this Wednesday 21.

The parties that are part of the hard liners in the opposition led by Antonio Ledezma, Oscar Perez, Oswaldo Alvarez Paz and Hermann Escarra continue, but probably not for long, to call for the cancellation of the referendum and abstention. It appears increasingly likely that the “reform” proposal will not pass. In such an event, but also in the case of a YES victory by a small margin, the political damage to Chávez will be irreversible.

Last Friday the anti-government candidates in the elections to the student bodies of the UCV received more than 4 times the votes of the Chavista slate. Chávez could however limit the damage to his hold on power and sidestep an unavoidable debacle by instructing the Supreme Tribunal of Justice to decide in favor of one of the sixteen requests before it to postpone or cancel the referendum.

However, Chávez also did say in a press conference to the foreign correspondents last week that “elections are just one strategic option in building socialism”. Tampering with the electronic voting machines is not likely to represent a great temptation, even if no international observers will be present on 2 December.

50% of the ballot boxes will be opened and their contents checked against the numbers of the corresponding voting machines. Opposition parties and ngo’s are organizing a nation-wide operation combining exit polls and a quick-count (tasks that are mainly being organized by Un Nuevo Tiempo).

A large part of the population, quite possibly half of it, feels that it is about to lose its identity, values and very livelihood, and is decided to vigorously defend its rights under any circumstance. The other half is split 3 to 2 between those that feel Chávez is not a bad person but that he is slightly off the rocker, and those that love him passionately and fear that rejection of the reform proposal would lead to the loss of their recently acquired benefits and political priority. But all generally agree that the “reform” proposal is not necessary to improve governance. Victory of the YES would spell deep instability, and victory of the NO is certainly no guarantee of normalcy.

The “reform” is proving to be Chávez gravest political mistake since his first election to the Presidency, and regardless of the results of the referendum his government will have lost its legitimacy as of the evening of 2 December. It will have been the result of a long and drawn out process that started even before his reelection last December, and which has been closely followed by the entire nation. This learning process bodes well for a relatively peaceful resolution of Venezuela’s grave crisis of governance.

Labels: Constitutional reform, Enrique ter Horst, Summary on Venezuela